While the plight of Cambodian-American deportees has gripped the community, the numbers pale compared to these other countries. In fiscal 2011, the most recent year for which data is available, 15 people were "removed" from the United States and sent to Cambodia. In 2010, it was 28.

Of course, that's small consolation if your loved one can never return to the land you call home.

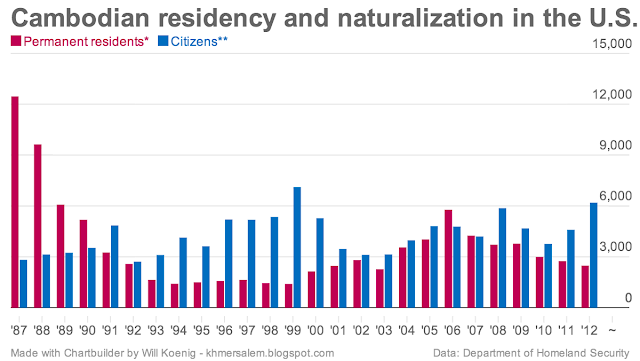

But that raises another question. If a relatively small number of Cambodian-Americans are being deported, and there are lots of ethnic Khmers in America, what is the status of everyone else?

- The initial high number of permanent residents captures the tail end of the wave of Cambodian resettlement in the United States. The Department of Homeland Security doesn't offer statistics before 1987 (that I have been able to find).

- Generally, you must become a permanent resident before becoming a citizen. Most people have to wait three to five years before applying for naturalization. People are likely counted twice in this graphic.

- Conditions in Cambodia dramatically improved in the 1990s, which may have encouraged Cambodian-Americans to get U.S. passports to return while simultaneously limiting Cambodian emigration to the U.S.

- There was a coup in 1997 that likely encouraged Cambodian-Americans to get U.S. passports so they could rely on the State Department for help escaping the kingdom. Likewise, that event certainly encouraged some Cambodians to emigrate.

- The DHS doubled most of its fees in July 2007, which may explain part of the peak in 2006 and subsequent decline. Or the decline in applications for permanent residency may be a result of more investigations into visa and marriage fraud.

No comments:

Post a Comment